By Cris Rhodes

Gene Luen Yang is the current Library of Congress Ambassador for Young People’s Literature

At this year’s Children’s Literature Association (ChLA) Conference, hosted by the Ohio State University in Columbus, Ohio, featured speaker Gene Luen Yang, author of Printz Award-winning American Born Chinese, presented conference attendees with a challenge—to read without walls. To do so, readers must read a book with characters unlike themselves, topics with which they are unfamiliar, and in a new format. As I listened to Yang’s challenge, I was thinking of ways I could encourage my colleagues to fulfill this challenge by reading Latinx children’s or young adult (YA) texts.

Certainly Latinx representation is starting to gain a foothold in the realm of children’s books. Examples including the Latinx representation in main character Noami, from Ashley Hope Pérez’s Out of Darkness, which was a Printz Award honor book. Pérez also gave a reading of Out of Darkness at this year’s ChLA conference, followed by a fascinating question and answer time, wherein scholars of all backgrounds engaged with Pérez’s text critically and discussed the writing and research processes.

Despite these productive conversations about important books like Out of Darkness, more needs to be done to gain visibility for diverse populations within the field of critical children’s literature studies. Inside the children’s literature community, diversity is slowly becoming more prominent, but Latinxs are still vastly underrepresented. Were more scholars to devote their time and talents to the study of Latinx literature or other diverse children’s literature, our field would be much more inclusive, and challenges like Yang’s would slowly become unnecessary.

However, as it stands, the ChLA conference is still in need of a liberal dose of diversity. Though ChLA is actively working to make its organization more inclusive, research on marginalized populations remains scarce. Just for a point of reference, there were six papers about the Harry Potter series alone, whereas there were only seven papers about Latinxs during the whole conference. This year, only two panels were entirely devoted to Latinx children’s literature and media—“Gender, Privilege, and Politics in Latino/a Texts and Media,” containing papers by Mauricio Espinoza and Domino Pérez, and “Brazilian Children’s Literature: from Illustration to Animation,” with papers by Renata Junqueira De Souza, Edgar Roberto Kirchof, and Rosa Maria Silveira. Individual scholars included Stacey Alex, Patricia Enciso and Ashley Hope Pérez, as well as Ann González, who was unable to present.

But, perhaps the most important panel of the entire conference was the career panel: “Needs of Minority Scholars.” Presented by four diverse scholars, including Laura Jiménez and Marilisa Jiménez Garcia, as well as Sarah Park Dahlen and Ebony Elizabeth Thomas, this panel fearlessly presented the truth about being a minority scholar in the field of children’s literature studies, education, and library science. After the panelists spoke, the room was opened up to questions, and quickly scholars of all backgrounds were sharing their experiences of heartbreak and triumph. While attending Ashley Hope Pérez’s reading the day before, I’d been thinking on and discussing representations of race-based trauma in literature, but little did I know that I’d bear witness to tales of trauma the very next day at the career panel. While many of the scholars attending the career panel spoke of the pitfalls of micro-aggression and exclusion in academia, there were also stories of hope, of scholars who felt supported despite great opposition. Through tears, many scholars, most of them women of color, bravely recounted their experiences to a room filled with love and support. As I listened to my colleagues speak, I, too, was fighting back tears. I’ve grown accustomed to being one of the only Latinas in a room of other children’s literature scholars; yet what this panel demonstrated was that I, and others like me, are not alone.

It is my deepest wish that we continue to encourage and nurture diverse scholars, particularly Latinxs. In order to gain the visibility that we so desperately need, we need to continue speaking up even if we’re afraid of the consequences. Afterward, I spoke to many panelists and participants in the minority scholars panel and the sentiment was much the same: they were afraid to share their experiences because to do so meant speaking out against the established ideologies of ChLA. Commenting later, Marilisa Jiménez Garcia explained that the panel was “one of the most difficult conversations I have ever had with an academic audience.” However, the positive outcomes of this discussion can and should outweigh the negative consequences.

Marilisa Jiménez-Garcia

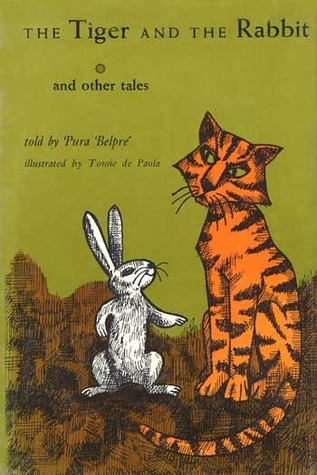

As many of the panelists and participants lunched and fellowshipped following the emotionally-charged conversation in the minority scholars panel, we received perhaps the greatest news of the weekend, that Marilisa Jiménez Garcia’s proposed panel on “The Rise of Latino/a Literature for Youth” for the 2018 Modern Languages Association’s conference, to be held in New York City, had been approved as ChLA’s one guaranteed session during that conference. What this acceptance demonstrates is that ChLA isn’t just saying that they value diversity and the study of Latinx children’s and YA literature, but they are actively promoting it and its study. I spoke with Jiménez Garcia following the conference and she explained, “It means a lot that this panel will be representing a vibrant part of children’s literature to the Modern Language Association,” because “Latinx Lit as a whole is underrepresented at MLA and English Lit conferences, so it makes the panel that much more significant.” Jiménez Garcia also spoke about her own personal connection to this research and the upcoming MLA conference location, stating: “In terms of New York, it is my research home, and a significant part of my childhood and life as an adult—-and you can’t talk about New York City without including the rich Latinx literary figures who wrote for young people here, including Jose Martí and Pura Belpré. Indeed, young Latinxs revolutionized the literary landscape in spaces like the Nuyorican Poet’s Cafe and Broadway, including Lin-Manuel Miranda’s revolutionary hip hop musical, Hamilton. Latinxs have been writing and rewriting the history of America through poetry and prose for generations in NYC.”

Reflecting on my experience at this year’s conference, I cannot help but feel a little vulnerable and still overwhelmed. I am scared that as we come down from the tense emotions of the weekend, we will lose the fervor to make change within our organization. But I am also happy and very hopeful that change is on the horizon. I think the inclusion of more and more Latinx scholars each year, and the addition of Ashley Hope Pérez’s amazing reading of her equally amazing book, are steps in the right direction. What becomes most important then, is that we keep up this momentum—that we make sure our voices are heard both within the organization and outside of it to demonstrate to other scholars that ChLA benefits from our perspectives. We need to open the door for other Latinxs and other marginalized peoples to ensure that there are always diverse scholars in the room.

Cris Rhodes is a doctoral student at Texas A&M University – Commerce. She received a M.A. in English with an emphasis in borderlands literature and culture from Texas A&M – Corpus Christi, and a B.A. in English with a minor in children’s literature from Longwood University in her home state of Virginia. Cris recently completed a Master’s thesis project on the construction of identity in Chicana young adult literature.

Cris Rhodes is a doctoral student at Texas A&M University – Commerce. She received a M.A. in English with an emphasis in borderlands literature and culture from Texas A&M – Corpus Christi, and a B.A. in English with a minor in children’s literature from Longwood University in her home state of Virginia. Cris recently completed a Master’s thesis project on the construction of identity in Chicana young adult literature.