By Cecilia Cackley

Whether we’re perusing the shelves at the library, walking into a bookstore or clicking on a tweet, the first part of the book we see is usually the cover. As more Latinx authors are publishing teen and children’s books, we’re also seeing more Latinx artists being featured on book covers. I was lucky enough to chat with four different artists about their creative process and how they got their start in publishing.

Cecilia Cackley: What first inspired you to become an artist?

Mirelle Ortega: I don’t think there was ever an “aha moment” for me. I’ve been drawing since I could hold a pen, and crafting stories has just always been my favorite thing to do. When my parents first asked me what I wanted to do when I grew up. I told them I wanted to make cartoons, so I think what inspired me to become an artist was just my sheer love for the art I saw in TV and books. Those stories and those drawings made me feel things, and I wanted to make people feel that way too.

Zeke Peña: I think comics and cartoons were really what inspired me to draw when I was young. Also my older brother was so good at drawing and I always looked up to him.

Jorge Lacera: Growing up, I always drew for fun. My mom worked in clothing factories and kept a stack of cardboard inserts that go in dress shirts in her purse. I’d draw on those whenever I’d get bored. I also knew my uncle in Colombia, where I was born, had at one point made a living as a graphic designer. I knew it was something I really wanted to do as an adult.

Kat Fajardo: Like most artists my age, I grew up with an obsession for anime and manga. I was a big fan of series like Digimon, Dragon ball Z, and Clamp manga series. They were unique and different compared to the classic cartoons and comics I grew up with like Tom & Jerry or Archie. I turned my admiration for that genre into creativity as I spent my free time sketching characters from these series, even taking requests from my classmates. Confident in my abilities, eventually I started creating my own characters and comics (which have been destroyed since then thankfully, they were really bad) and decided that I wanted to be an artist when I grow up. Several years later after honing my skills and experience in art high school and art college, I’ve been making comics and illustrations since then.

CC: How did you become a cover artist specifically? Did an art director reach out to you, or did you submit samples for a particular book?

Mirelle: For Love, Sugar, Magic I was lucky enough to be approached by the publishing house after Anna (the author) found samples of my work on social media. For other projects, it’s been through the agency I am represented by. Sometimes it requires me to do art tests for projects, especially when the client wants something that they don’t specifically see in any of your sample work.

Jorge: I was actually approached by designer Kate Renner at Viking Penguin via email. She had seen my portfolio and knew from my bio that I grew up in South Florida (where The Epic Fail of Arturo Zamora takes place).

Kat: I didn’t get into cover design until I started working with my agent Linda Camacho. Unlike me, she is well-versed in the YA publishing world, so it was nice to have that access to the industry through her. I was able to find freelance work such as The First Rule of Punk book and working on Disney’s Isle of the Lost. So if anyone is looking to do cover design work specifically, I recommend hiring an agent in that field, it’s incredibly useful!

Zeke: I started doing cover illustration in the music industry for bands and community organizing campaigns. This experience is really what helped me develop my style and understanding of covers. Then in 2014 Cinco Puntos Press in El Paso reached out to me to do my first published work for a book cover.

CC: When you get hired to create a cover, do you get to read the book before doing the artwork?

Mirelle: Sometimes.

Zeke: When I have time, I like to read the text, but sometimes timelines and my workload don’t allow that. So I’ll usually ask editors and art directors to suggest excerpts to read that will give me a good sense of the scene or character I’m illustrating. I like to do this because it helps me visualize things while I’m working.

If it is a children’s book, yes, because I will also be making all the illustrations for the interior art. Even if it’s just partially illustrated.

For middle grade, sometimes you get a manuscript and other times you get just a couple pages or a chapter or two and a detailed description of the characters. Sometimes even a mood board with things that inspired the manuscript itself.

Jorge: Yes. I was sent a sample at first and eventually a PDF of the book to read. Both Kate and Joanna had ideas for how they wanted the cover to feel inspired by passages from the book itself. For our second cover for Pablo Cartaya, I was sent the entire manuscript upfront, and I read it all in one sitting late into the the night.

Kat: If my schedule allows it, I try my very best to read as much of the material as possible to get some ideas or feel for the piece, which is why most editors provide that material for designers. Although, for The First Rule of Punk, it was super cool to have read the first draft of the book and even the pitch material (it had a really cute comic explaining the synopsis of the book by Celia). It was Celia’s debut book, so it was an honor to have been able to read it before the public.

CC: For books with Latinx themes, how do you decide whether or not to include specific cultural imagery? Do you get to decide that or is it something the author or editor weighs in on?

Jorge: It’s a collaboration. The Editor, Art Director/Graphic Designer, and I usually have a conversation to kick things off, and they always have great ideas for things they want to see. I then read the manuscript and come up with additional ideas based on the themes and imagery that jumps out at me. I think the most important thing is for the art to feel authentic to the story and make a person walking by want to pick it up.

Mirelle: In my experience, the art directors of the projects always have some specific cultural imagery they want you to incorporate, but they’ve also been very open to hear if I have a different idea or if there’s anything I feel strongly that should be included.

That said, I do get to pick a lot of the things that appear in the background and how the characters look and dress, and I always try to think of specifics about the characters whenever I can. There is a lot of beautiful diversity within the Latinx community, and I am always trying to make people feel represented, or show parts of it that I haven’t seen a lot of in media.

Kat: Depending on whether Latinx imagery is essential to the story, I aim to include some cultural elements to my pieces. But for The First Rule of Punk I was very lucky to have worked with a team that understood Latinx imagery was essential to the book. Thankfully they already had a list of illustrations to include such as Worry Dolls (a handmade doll found in Mexico and Guatemala), Traditional Mexican rebozo, Olmec heads, Calacas (Day of the Dead skulls), coconuts, quetzal birds, punk band references, Lotería cards, etc. I thought, wow this is a perfect bridge to Latinx culture and zines, all I needed to add was a delicious Concha (Mexican sweet bread) and this Mexican punk cover is all set to go! Which I did and the team loved it.

Zeke: I think it is a sum of all things. I definitely have a strong sense of what I want to do but editors will usually weigh in on whether or not I’m getting something right. The process is collaborative, and I think that only helps make the work stronger so that any ideas of culture are treated appropriately.

CC: I asked each artist to talk a little about a specific cover they had created, including how many versions they went through, their creative process, etc.

Mirelle on the book Love Sugar Magic by Anna Meriano: I come from a background in Animation, so I always start by designing the main character. I did a billion doodles of Leo on my notebook and then sent over some options. From there, I did a few sketches of the composition, and there was some back and forth with some tweaks here and there. Most of the sketches I did were digital, so they were really easy to tweak.

Jorge on the book The Epic Fail of Arturo Zamora by Pablo Cartaya: After my initial conversation with Joanna and Kate, I went back and did several rounds of thumbnails, exploring different approaches to color and subjects from the book. After a round of internal feedback from various departments at Viking, including Marketing, we ended up moving away from the initially approved direction. This is ok and totally part of the process. Luckily, we very quickly arrived at the idea of Arturo pushing the text. After that it went pretty quickly to final.

Kat on the book The First Rule of Punk by Celia C. Pérez: The process of creating The First Rule of Punk cover involved a ton of revisions and notes between myself, the editor, project designer, and the writer. In the beginning, Celia had a couple of fantastic ideas for her cover design, and she was inspired by fun series like Roller Girl by Victoria Jamieson. The first idea was based on the cover from my zine Gringa!. As fans of the zine, the editorial team loved the idea of a literal split of two cultures for Malú (one side being traditionally Mexican and the other is punk) and thought something similar to that would work with the story. The second idea was the direction we took with the final image which echoed the more traditional cut and paste approach of images found in zines. In the original design, Celia had a cute stick figure surrounded by beautiful cut out flowers on a yellow background. Inspired by this design, I took it further with having photocopied cut-out images of certain story elements. After the first rounds of sketches based on both ideas, we eventually went with the design of the current cover. Since it was my first middle grade project, and I had been working in indie comics by then, I didn’t realize Malú looked older in the original sketches until the editor had pointed it out. After that, for each revision, I made sure to age her down a bit, which sounds silly, but it’s an incredibly important lesson to learn when working in the children’s literature industry. As with the final image, Celia and the editorial team loved the lightning illustrations I added as the finishing touch. Though the entire process took a couple of months, it was very rewarding working with this team! A year later, I had the luck to work with them again for the tip-in illustrations which could be found in the newest hardcover editions.

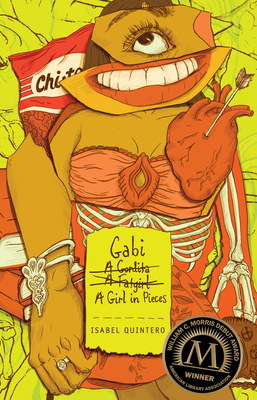

Zeke on the book Gabi: a Girl in Pieces by Isabel Quintero: I had the unique opportunity to be in direct contact with the author, so the process was very collaborative. Isabel gave me lots of feedback and even sent over some collages she made as inspiration. I usually sketch thumbnails then go to a larger pencil sketch. For this cover, I had lots of great ideas, so there were a lot of compositions that I tried out. Actually, I have a version that I would love to use for something. It has more of a comic book feel to it. The final cover, I think, had about 5 or 6 versions that varied in composition and scale. I picked some bright colors, so the book would stand out on the shelf and did some custom hand-drawn typography for the title. Not many people know, but I also drew the zines on the inside of the book based on Isabel’s collages, and I designed the layout for the book.

CC: Imagine you could create a cover for any Latinx writer working today. Who would you want to work with?

Mirelle: I honestly would be happy creating cover art for every Latinx writer out there, well-established or newcomers. As long as their story moves me, I want to be a part of it!

Kat: A while back, I did get the chance to redraw one of my favorite writer’s book cover, Gabby Rivera’s Juliet Takes a Breath for Disney-Hyperion. In the end, the editor decided to go with the original cover artist, which was a great decision considering I’m big fan of Cristy C. Road’s work (she did an absolute perfect job on the first cover). However, it was a huge honor to have been chosen to work on Rivera’s book cover, though I would love to work with her again in the future and hopefully meet in person!

Zeke: I would love to collaborate on making a cover with Lilliam Rivera, Elizabeth Acevedo, and Luis Alberto Urrea.

Jorge: I’m a big fan of the work of Meg Medina, and it would be incredible to get to illustrate one of her covers. It would be really cool to have the opportunity to illustrate one of Daniel José Older’s books since I’m such a fan of scifi and fantasy. Guillermo Del Toro’s work is a big influence on me and I know he’s written a few things, and I’d be honored to collaborate with J.C. Cervantes.

CC: Thank you all so much for chatting with me! Any upcoming projects (cover art or other work) that we should know about?

Mirelle: Yes! I’m illustrating a series of books called Gavin McNally’s Year Off that will be out next year! And, there’s a beautiful Latinx project in the works, but I can’t really talk about it yet.

Kat: I’m excited to share that I’m signing with a children’s publisher for my first solo graphic novel. I can’t say too much about it at the moment, but it’s going to be a semi-autobiographical coming of age story taking place in Honduras. Having spent every summer there as a kid, rather than hanging out with friends back in the US, this book is a love letter to my culture and all the painful experiences I had growing up there as a “weird Gringa”. I hope readers with similar backgrounds will identify with the story and know they are not alone. And to be honest, I don’t see much positive representation for Central Americans in US media. I really hope this book can shed some light on the lovely and honest lives of the folks living there. With that said, I’m super excited to show readers that embarrassing side of myself and my family; it’s going to be really fun.

Zeke: Yes, my first children’s picture book written by Isabel Quintero will be published in 2019 by Kokila a Penguin Books imprint. I’m also working on an illustrated project about the river in my border community of El Paso and Ciudad Juárez.

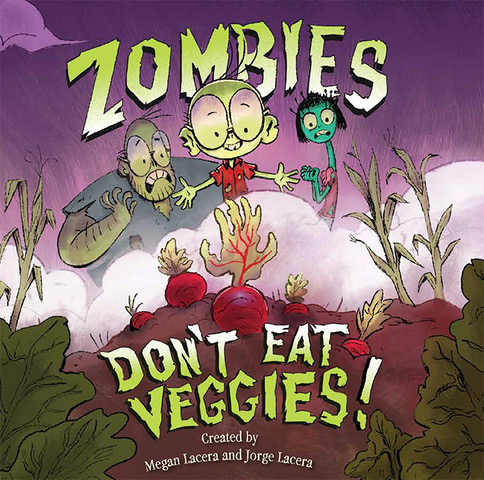

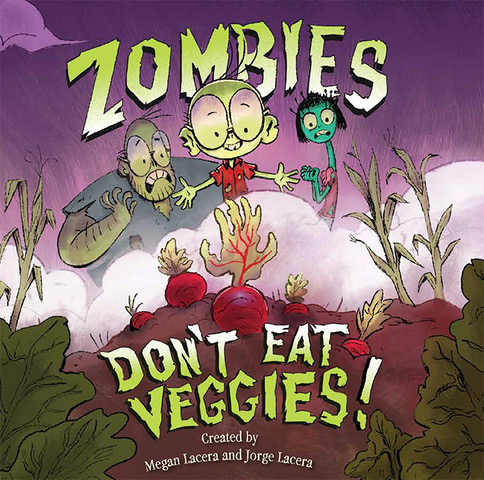

Jorge: Why yes! My wife Megan Lacera and I have our first picture book coming out in April 2019 from Lee and Low. It is called Zombies Don’t Eat Veggies! Megan wrote it and I illustrated it. It’s about Mo Romero a zombie who loves nothing more than growing, cooking, and eating vegetables. Tomatoes? Tantalizing. Peppers? Pure perfection! The problem? Mo’s parents insist that their niño eat only zombie cuisine, like arm-panadas and finger foods. They tell Mo over and over that zombies don’t eat veggies. But Mo can’t imagine a lifetime of just eating zombie food and giving up his veggies. As he questions his own zombie identity, Mo tries his best to convince his parents to give peas a chance.

Very excited that our book will be released in both English and Spanish simultaneously.

I’m also thrilled to be illustrating a book by Deborah Underwood for Disney Hyperion as well as a book by Nancy Viau for Two Lions publishing.

ABOUT THE ARTISTS:

Zeke Peña is a cartoonist and illustrator working on the United States/Mexico frontera in El Paso, Tejas. He makes comics to remix history and reclaim stories using satire and humor; resistencia one cartoon at a time. He recently received the Boston Globe Horn Book Award for a graphic biography he illustrated titled Photographic: The Life of Graciela Iturbide (Getty Publications 2017). Zeke studied Art History and Visual Culture at the University of Texas Austin. He has published work with VICE.com, Latino USA, The Believer Magazine, The Nib, Penguin Random House, Holt/Macmillan and Cinco Puntos Press. He is currently working on a children’s book written by Isabel Quintero to be published in 2019 by Kokila, a Penguin Books imprint.

Zeke Peña is a cartoonist and illustrator working on the United States/Mexico frontera in El Paso, Tejas. He makes comics to remix history and reclaim stories using satire and humor; resistencia one cartoon at a time. He recently received the Boston Globe Horn Book Award for a graphic biography he illustrated titled Photographic: The Life of Graciela Iturbide (Getty Publications 2017). Zeke studied Art History and Visual Culture at the University of Texas Austin. He has published work with VICE.com, Latino USA, The Believer Magazine, The Nib, Penguin Random House, Holt/Macmillan and Cinco Puntos Press. He is currently working on a children’s book written by Isabel Quintero to be published in 2019 by Kokila, a Penguin Books imprint.

Mirelle Ortega is an illustrator and concept artist currently living in California. She’s originally from the south east of Mexico, and has a passion for storytelling, sci-fi, film, tv, color and culture. Mirelle has a BFA from the Tecnológico de Monterrey (Monterrey, Mexico) in digital art and 3D animation, and a MFA from Academy of Art University in San Francisco.

Mirelle Ortega is an illustrator and concept artist currently living in California. She’s originally from the south east of Mexico, and has a passion for storytelling, sci-fi, film, tv, color and culture. Mirelle has a BFA from the Tecnológico de Monterrey (Monterrey, Mexico) in digital art and 3D animation, and a MFA from Academy of Art University in San Francisco.

Jorge Lacera was born in Colombia and grew up drawing and painting in sketchbooks, on napkins, on walls, and anywhere his parents would let him in Miami, Florida.

Jorge Lacera was born in Colombia and grew up drawing and painting in sketchbooks, on napkins, on walls, and anywhere his parents would let him in Miami, Florida.

After graduating with the honor of ‘Best of Ringling’ from Ringling College of Art and Design, Jorge chose to ‘Flee to the Cleve’ where he worked as a visual development artist and IP creator at American Greetings in Cleveland, Ohio. There he met Megan, his wife and Studio Lacera partner-in-crime. They’ve been creating and collaborating together ever since.

Jorge was formerly the Lead Concept Artist at award-winning Irrational Games.

Kat Fajardo is an award-winning comic artist and illustrator based in NYC. A graduate of The School of Visual Arts, she’s editor of La Raza Anthology and creator of Bandida Comics series. She’s created work for Penguin Random House on The First Rule of Punk (written by Celia C. Pérez), CollegeHumor, and several comic anthologies. You can find her working at her Brooklyn studio creating playful and colorful work about self-acceptance and Latinx culture.

Kat Fajardo is an award-winning comic artist and illustrator based in NYC. A graduate of The School of Visual Arts, she’s editor of La Raza Anthology and creator of Bandida Comics series. She’s created work for Penguin Random House on The First Rule of Punk (written by Celia C. Pérez), CollegeHumor, and several comic anthologies. You can find her working at her Brooklyn studio creating playful and colorful work about self-acceptance and Latinx culture.

Cecilia Cackley is a Mexican-American playwright and puppeteer based in Washington, DC. A longtime bookseller, she is currently the Children’s/YA buyer and event coordinator for East City Bookshop on Capitol Hill. Find out more about her art at www.ceciliacackley.com or follow her on Twitter @citymousedc

Cecilia Cackley is a Mexican-American playwright and puppeteer based in Washington, DC. A longtime bookseller, she is currently the Children’s/YA buyer and event coordinator for East City Bookshop on Capitol Hill. Find out more about her art at www.ceciliacackley.com or follow her on Twitter @citymousedc

Zeke Peña is a cartoonist and illustrator working on the United States/Mexico frontera in El Paso, Tejas. He makes comics to remix history and reclaim stories using satire and humor; resistencia one cartoon at a time. He recently received the Boston Globe Horn Book Award for a graphic biography he illustrated titled Photographic: The Life of Graciela Iturbide (Getty Publications 2017). Zeke studied Art History and Visual Culture at the University of Texas Austin. He has published work with VICE.com, Latino USA, The Believer Magazine, The Nib, Penguin Random House, Holt/Macmillan and Cinco Puntos Press. He is currently working on a children’s book written by Isabel Quintero to be published in 2019 by Kokila, a Penguin Books imprint.

Zeke Peña is a cartoonist and illustrator working on the United States/Mexico frontera in El Paso, Tejas. He makes comics to remix history and reclaim stories using satire and humor; resistencia one cartoon at a time. He recently received the Boston Globe Horn Book Award for a graphic biography he illustrated titled Photographic: The Life of Graciela Iturbide (Getty Publications 2017). Zeke studied Art History and Visual Culture at the University of Texas Austin. He has published work with VICE.com, Latino USA, The Believer Magazine, The Nib, Penguin Random House, Holt/Macmillan and Cinco Puntos Press. He is currently working on a children’s book written by Isabel Quintero to be published in 2019 by Kokila, a Penguin Books imprint. Jorge Lacera was born in Colombia and grew up drawing and painting in sketchbooks, on napkins, on walls, and anywhere his parents would let him in Miami, Florida.

Jorge Lacera was born in Colombia and grew up drawing and painting in sketchbooks, on napkins, on walls, and anywhere his parents would let him in Miami, Florida. Kat Fajardo is an award-winning comic artist and illustrator based in NYC. A graduate of The School of Visual Arts, she’s editor of La Raza Anthology and creator of Bandida Comics series. She’s created work for Penguin Random House on The First Rule of Punk (written by Celia C. Pérez), CollegeHumor, and several comic anthologies. You can find her working at her Brooklyn studio creating playful and colorful work about self-acceptance and Latinx culture.

Kat Fajardo is an award-winning comic artist and illustrator based in NYC. A graduate of The School of Visual Arts, she’s editor of La Raza Anthology and creator of Bandida Comics series. She’s created work for Penguin Random House on The First Rule of Punk (written by Celia C. Pérez), CollegeHumor, and several comic anthologies. You can find her working at her Brooklyn studio creating playful and colorful work about self-acceptance and Latinx culture. Cecilia Cackley is a Mexican-American playwright and puppeteer based in Washington, DC. A longtime bookseller, she is currently the Children’s/YA buyer and event coordinator for East City Bookshop on Capitol Hill. Find out more about her art at

Cecilia Cackley is a Mexican-American playwright and puppeteer based in Washington, DC. A longtime bookseller, she is currently the Children’s/YA buyer and event coordinator for East City Bookshop on Capitol Hill. Find out more about her art at  DESCRIPTION OF THE NOVEL:

DESCRIPTION OF THE NOVEL: