By Cecilia Cackley

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Cecilia Cackley: This is your twenty-first picture book! You’ve written three of them yourself, but you’ve also worked with a wide range of collaborators. How do you feel like your process has evolved as an artist?

Lauren Castillo: It feels like I’m choosing a different medium for each project, but somehow it ends up looking like the same type of art to others. Imagine for instance, doesn’t look too different from Nana in the City, but to me, I definitely worked in a lot of different ways to make the art. For example, because this book had so many landscapes, I really wanted to embrace that imperfect, texture-y feeling in a more abstract way. I wanted to have a looser style, so I used something that I had been playing around with in workshops with children—printmaking by painting on foam. It’s really fun because you don’t know what you’re going to end up with until you run the print. That’s kind of the beauty of printmaking, that nothing is going to be exact and precise. I think my art, over the years, felt like I was tightening up and it felt a little too crafted. I think it was because my drawing wasn’t as strong at first, so it gave this energetic, free feeling to the work and I liked that. I’ve been trying to figure out ways to trick myself into loosening up. For this book it was helpful to use this type of printmaking for the backgrounds. I would paint on the foam and then flip it over and stamp it on the paper. I work in a much smaller scale so when it’s enlarged it gets even more texture. With each book I need to use different types of materials to keep things interesting.

CC: Is this your first non-fiction picture book about a living person?

LC: Yes.

CC: How was the research process different than for, say, your book about E.B. White?

LC: It was very different! I did not interact at all with Juan directly. I sent some questions through the publisher Candlewick because it was a poem and it was non-descriptive in terms of the locations and the years and that sort of thing. I had this vision for it so I didn’t want to know too many details but I wanted to gauge the era, the decade and the locations that he was speaking about. I had looked at some photographs of him and most were current so I decided, although I probably could have gotten some childhood photos of him, to do my own version of him and what I imagined he looked like when he was younger. So the character development was done without photo reference. But they gave me some locations to work with so I could get photos from the computer for those. It was a lot freer than working on E.B. White’s life, for example, because that was very descriptive and specific, even down to the animals that were in the barn.

CC: Would you say this is the most poetic text you’ve ever worked on?

LC: Probably. I would definitely call some of the other books I’ve worked on poetic, or poems but this feels most definitely like it was pulled out of a poetry book and it’s gorgeous. The first time I read it I thought “Well, I have to illustrate this!”

CC: Tell us a little about your own Latinx family background.

LC: My dad’s father is Cuban, and my mom’s mom is Puerto Rican.

CC: Is this the first book by another Latinx author that you’ve worked on?

LC: It is, which I was very excited about. I grew up asking a lot of questions about my grandparents’ lives and their parents’ lives, coming to the United States, and it seemed like I was more interested in my background and culture than a lot of my friends. I did a lot of reports as a kid, interviewing my grandparents. I would be curious to see how connected to my art Juan Felipe was, if there was anything that reminded him of his own life or if I took liberties that were very different. It would be interesting to have a conversation about it.

CC: Do you think that you’ll ever make any work connected with your own family history?

LC: My Puerto Rican great-grandfather was a musician, and when he moved to New York, his family lived in the Spanish Harlem area. My grandmother told me stories about when she was young and he had a band that would play around different venues in Spanish Harlem. So when I moved to New York for graduate school, we had to do a book project, and I decided I wanted to do a visual journalism project about this really old music store in Spanish Harlem called Casa Latina. I went there and asked them if I could spend a month coming in and out of their store and do drawings, so basically I did this whole visual journalism project that I turned into a book about the people in the store and how they interacted with each other and their customers. I would have conversations with them and take notes, so it was kind of like a diary, but it included drawings from the shop and portraits of people that work there, and I called it Casa Latina. I’ve wanted to turn that into a picture book at some point because when I was going to the store I had it in my mind that although that store wasn’t around then, that’s the same neighborhood that my great-grandfather was spending a lot of time in and playing music in. So I got really invested in that area, and for a while, I’ve been keeping some drafts of stories that I want to do, some ideas to turn that project into a picture book. So yes, I definitely want to do a project that connects to that Puerto Rican background.

CC: What are you working on now?

LC: At the moment I’m working on a very unusual project for me, which is completely imagined, because so far, my three picture books have all come from some sort of life experience, and so I’m working on this early chapter book. It’s about the hedgehog character that I had drawn that kept popping up in my sketchbook, and it’s all animals and one human character, and it’s very much a made up story. And also it’s a long format book, which is a lot of fun since I don’t have a lot experience with that!

MORE ABOUT LAUREN CASILLO: Lauren studied illustration at the Maryland Institute College of Art and received her MFA from the School of Visual Arts in New York City. She is the author and illustrator of the 2015 Caldecott Honor winning book, Nana in the City, as well as The Troublemaker and Melvin and the Boy. Lauren has also illustrated several critically acclaimed picture books, including Twenty Yawns by Jane Smiley, Yard Sale by Eve Bunting, and City Cat by Kate Banks. She currently draws and dreams in Harrisburg, PA. You can find out more about her at http://www.laurencastillo.com/

Cecilia Cackley is a Mexican-American playwright and puppeteer based in Washington, DC. A longtime bookseller, she is currently the Children’s/YA buyer and event coordinator for East City Bookshop on Capitol Hill. Find out more about her art at www.ceciliacackley.com or follow her on Twitter @citymousedc

Cecilia Cackley is a Mexican-American playwright and puppeteer based in Washington, DC. A longtime bookseller, she is currently the Children’s/YA buyer and event coordinator for East City Bookshop on Capitol Hill. Find out more about her art at www.ceciliacackley.com or follow her on Twitter @citymousedc

DESCRIPTION FROM THE PUBLISHER:

DESCRIPTION FROM THE PUBLISHER:  ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:  DESCRIPTION FROM THE PUBLISHER:

DESCRIPTION FROM THE PUBLISHER:  ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Hilda Eunice Burgos

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Hilda Eunice Burgos  DESCRIPTION OF THE BOOK: Marcus Vega is six feet tall, 180 pounds, and the owner of a premature mustache. When you look like this and you’re only in the eighth grade, you’re both a threat and a target.

DESCRIPTION OF THE BOOK: Marcus Vega is six feet tall, 180 pounds, and the owner of a premature mustache. When you look like this and you’re only in the eighth grade, you’re both a threat and a target. ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Pablo Cartaya is an award-winning author whose books have been reviewed by The New York Times, featured in The Washington Post, received starred reviews from Kirkus, Booklist, Publisher’s Weekly, and School Library Journal, as well as been among the Best Books of the Year for Amazon, Chicago Public Library, NYPL, and several state award lists. He Is the author of the critically acclaimed middle grade novels The Epic Fail of Arturo Zamora (a 2018 Pura Belpré Honor Book) and Marcus Vega Doesn’t Speak Spanish. His next novel, Each Tiny Spark will debut on the new Kokila Penguin/Random House Imprint, which focuses on publishing diverse books for children and young adults. He teaches at Sierra Nevada College’s MFA program in Writing and visits schools and colleges around the country. Pablo is proudly bilingual en español y ingles. @phcartaya

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Pablo Cartaya is an award-winning author whose books have been reviewed by The New York Times, featured in The Washington Post, received starred reviews from Kirkus, Booklist, Publisher’s Weekly, and School Library Journal, as well as been among the Best Books of the Year for Amazon, Chicago Public Library, NYPL, and several state award lists. He Is the author of the critically acclaimed middle grade novels The Epic Fail of Arturo Zamora (a 2018 Pura Belpré Honor Book) and Marcus Vega Doesn’t Speak Spanish. His next novel, Each Tiny Spark will debut on the new Kokila Penguin/Random House Imprint, which focuses on publishing diverse books for children and young adults. He teaches at Sierra Nevada College’s MFA program in Writing and visits schools and colleges around the country. Pablo is proudly bilingual en español y ingles. @phcartaya ABOUT THE REVIEWER: Mimi

ABOUT THE REVIEWER: Mimi

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

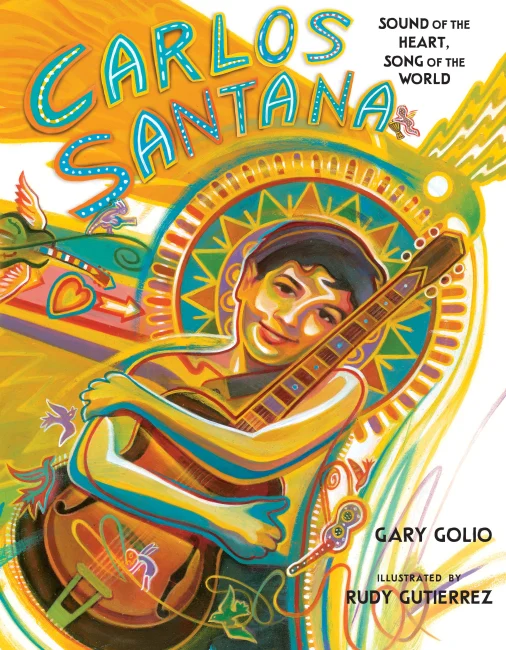

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:  ABOUT THE ILLUSTRATOR: Rudy Gutierrez is the distinguished creator behind the cover art for Santana’s multiplatinum album Shaman and the recently released

ABOUT THE ILLUSTRATOR: Rudy Gutierrez is the distinguished creator behind the cover art for Santana’s multiplatinum album Shaman and the recently released  ABOUT THE REVIEWER:

ABOUT THE REVIEWER:  DESCRIPTION OF THE BOOK: Stella Diaz loves marine animals, especially her betta fish, Pancho. But Stella Diaz is not a betta fish. Betta fish like to be alone, while Stella loves spending time with her mom and brother and her best friend Jenny. Trouble is, Jenny is in another class this year, and Stella feels very lonely. When a new boy arrives in Stella’s class, she really wants to be his friend, but sometimes Stella accidentally speaks Spanish instead of English and pronounces words wrong, which makes her turn roja. Plus, she has to speak in front of her whole class for a big presentation at school! But she better get over her fears soon, because Stella Díaz has something to say!

DESCRIPTION OF THE BOOK: Stella Diaz loves marine animals, especially her betta fish, Pancho. But Stella Diaz is not a betta fish. Betta fish like to be alone, while Stella loves spending time with her mom and brother and her best friend Jenny. Trouble is, Jenny is in another class this year, and Stella feels very lonely. When a new boy arrives in Stella’s class, she really wants to be his friend, but sometimes Stella accidentally speaks Spanish instead of English and pronounces words wrong, which makes her turn roja. Plus, she has to speak in front of her whole class for a big presentation at school! But she better get over her fears soon, because Stella Díaz has something to say! ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:  ABOUT THE REVIEWER: Jessica Agudelo is a Children’s Librarian at the New York Public Library. She has served on NYPL’s selection committee for its annual 100 Best Books for Kids list, most recently as a co-chair for the 2018 list. She contributes reviews for School Library Journal of English and Spanish language books for children and teens, and is a proud member of the Association of Library Services to Children, Young Adult Library Services Association, and REFORMA (the National Association to Promote Library and Information Services to Latinos and Spanish Speakers). Jessica is Colombian-American and born and raised in Queens, NY.

ABOUT THE REVIEWER: Jessica Agudelo is a Children’s Librarian at the New York Public Library. She has served on NYPL’s selection committee for its annual 100 Best Books for Kids list, most recently as a co-chair for the 2018 list. She contributes reviews for School Library Journal of English and Spanish language books for children and teens, and is a proud member of the Association of Library Services to Children, Young Adult Library Services Association, and REFORMA (the National Association to Promote Library and Information Services to Latinos and Spanish Speakers). Jessica is Colombian-American and born and raised in Queens, NY.