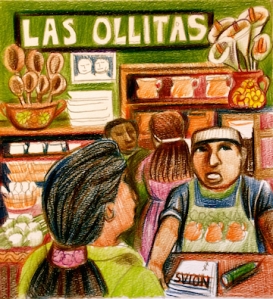

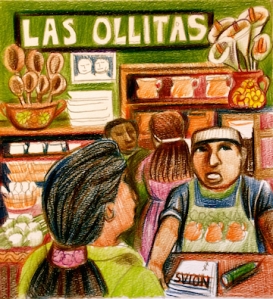

All art in this article is by Daniel Comacho for Joelito’s Big Decision/La gran decisión de Joelito by Ann Berlak.

By Ann Berlak

To prepare children and young people to participate in the construction of a more just and joyful future, we must tell them stories that make the invisible visible and unsettle what is taken for granted.

“Everything in the mainstream media suggests that popular resistance is ridiculous…unless it is far away, long ago.”

Solnit (2016)

Poverty is increasing worldwide in the face of unimaginable wealth for the very few. Talk of the public good has been almost silenced, public services are rapidly being privatized and the environment degraded, and we have come to take as normal wars without end. Yet, though largely obscured by mainstream media and by schooling at all levels, movements for climate, racial, and economic justice are sweeping the globe.

Given these realities, what stories should we tell young people to prepare them to participate in social transformation?

Stories that reveal:

- how the decisions and actions of each of us affect the lives and actions of others, often in hidden ways

- how differences of power in the hierarchies of race, class, gender, sexual orientation, and disability—differences that may be initially invisible– affect how we and others experience our lives differently (empathy)

- how to connect the dots between everyday injustices and the social forces that create and sustain them—for example, societal dynamics that create the vast extremes of wealth and poverty

- how ordinary people acting together can create a more just and joyful world

- that joining with others to create a more just future is a joyful life option for each of us

Aren’t children too young to think about social and political issues? Should we interfere with children’s innocence by prematurely exposing them to the darker sides of life?

Aren’t children too young to think about social and political issues? Should we interfere with children’s innocence by prematurely exposing them to the darker sides of life?

Which children are we talking about here? Certainly not those children who already experience despair, who go to bed hungry, whose parents can’t find jobs. Acknowledging these realities means acknowledging the experiences of children and young people who are often marginalized in school and in children’s fiction.

When adults are silent about the social, political, and economic dynamics of society, children internalize the perspectives that dominate public discourse and begin to believe, for example, that people get rich because they are smarter or work harder. They learn to blame “the victim,” and to normalize war, violence, and astounding inequalities.

This is disastrous for privileged children as well as for members of groups that are on the downside of the prevailing power imbalances. Both groups drift toward the belief that this is how things have always been and how they must continue to be, and these convictions become quite resistant to change. As the tree is bent, the tree grows.

Joelito’s Big Decision/ La gran decisión de Joelito

Joelito’s Big Decision/ La gran decisión de Joelito

For thirty years, I taught prospective elementary school teachers. My primary intention was to challenge them to think about what kind of future they wanted to construct through what they taught. What should schooling in their classrooms be for, beyond preparing children to be “college and career ready”?

After I retired, I went back into classrooms as a guest social-justice teacher. This experience reconfirmed my belief that if given any encouragement at all, children and young people will eagerly engage in dialogue about the social, political, and economic issues that surround and shape them.

I also realized that when adults don’t address these issues, children construct their own explanations for what they see around them, and that they weave these from the dominant ideologies of the society. For example, the children I taught had a variety of explanations for how and why some people get rich: They “won the lottery,” “worked hard at school,” “were really smart.” Of course, many also believed the inverse—that people who are poor do not work hard, or are not smart—even when these beliefs conflicted with their own first-hand experiences.

Eventually, I decided to write a storybook for children that would help teachers and parents spark lively conversations like the ones I had as a social-justice teacher, and elicit looks of surprise that conveyed “ah-ha” experiences that are our rewards as teachers. The result is the bilingual, beautifully illustrated and timely Joelito’s Big Decision/ La gran decisión de Joelito. It’s about a boy, a burger, a friendship, and the fight to raise the minimum wage. The book’s illustrator is Daniel Camacho. José Antonio Galloso provided the translation.

Our book tells the tale of Joelito, who eats dinner at MacMann’s Burger Restaurant with his family every Friday. The story begins one Friday when he finds his best friend Brandon and Brandon’s parents at the restaurant entrance, holding up signs saying, “Low Pay is Not OK,” and “Fight for 15,” and urging the hungry Joelito not to eat at MacMann’s tonight.

Our book tells the tale of Joelito, who eats dinner at MacMann’s Burger Restaurant with his family every Friday. The story begins one Friday when he finds his best friend Brandon and Brandon’s parents at the restaurant entrance, holding up signs saying, “Low Pay is Not OK,” and “Fight for 15,” and urging the hungry Joelito not to eat at MacMann’s tonight.

Our book explains the sources of income inequality in a way that young children can understand—Brandon’s dad tells Joelito, “I would have to work for 500 years to earn what Mr. MacMann earns in one year” —and shows that people working together are making history today.

Why don’t parents and teachers talk more about economic inequality with children and young people?

The school curriculum is increasingly controlled by the 1%. This control militates against schools teaching children and young people to question the huge discrepancies of wealth and power. Because the structure of our economy offers most people an uncertain economic future, many parents are preoccupied with their children becoming “college and career ready.” Readiness is often reduced to achieving high scores on standardized tests, while preparing children for active citizenship and critical thinking increasingly falls by the wayside.

Hope

Hope

We hope that literary gatekeepers—parents, teachers, caregivers, and librarians— will include among the stories that they share with children depictions of ordinary people working together toward a better future. The bookshelves in our classrooms, libraries, and homes are crowded with the tales of solitary heroes and heroines fighting battles in worlds of fantasy, mystery, and historical fiction. Stories of contemporary people in the trenches for social change belong on those bookshelves, too.

Author Ann Berlak has been a teacher and teacher educator for over fifty years. She envisions schools as places where children learn to become active, caring participants in the creation of a world that works for everyone. Joelito’s Big Decision/La gran decisión de Joelito was selected for the 2016-2017 California Reads list of teacher recommended books. Keep up with current news about Joelito on Facebook.

Author Ann Berlak has been a teacher and teacher educator for over fifty years. She envisions schools as places where children learn to become active, caring participants in the creation of a world that works for everyone. Joelito’s Big Decision/La gran decisión de Joelito was selected for the 2016-2017 California Reads list of teacher recommended books. Keep up with current news about Joelito on Facebook.

Illustrator Daniel Camacho lives and works in Oakland, California. His at-home studio is filled with ongoing projects, and is usually open to visitors upon request. He teaches art to elementary and middle school students and works to promote an awareness of Mexican/Latino culture through his participation with the Oakland Museum of California, the Spanish Speaking Unity Council, local public libraries and other community based organizations. Learn more about Daniel from his official website.

Translator José Antonio Galloso was born in Lima, Peru. He is a writer, photographer, and a bilingual teacher with studies in audiovisual communication, Spanish, and writing. He has published poetry and fiction and his works have been included in several anthologies. His photographic work, which he considers an extension of his writing, has been exhibited and published in different galleries, printed media and online. He has been living in the Bay Area since 2002.

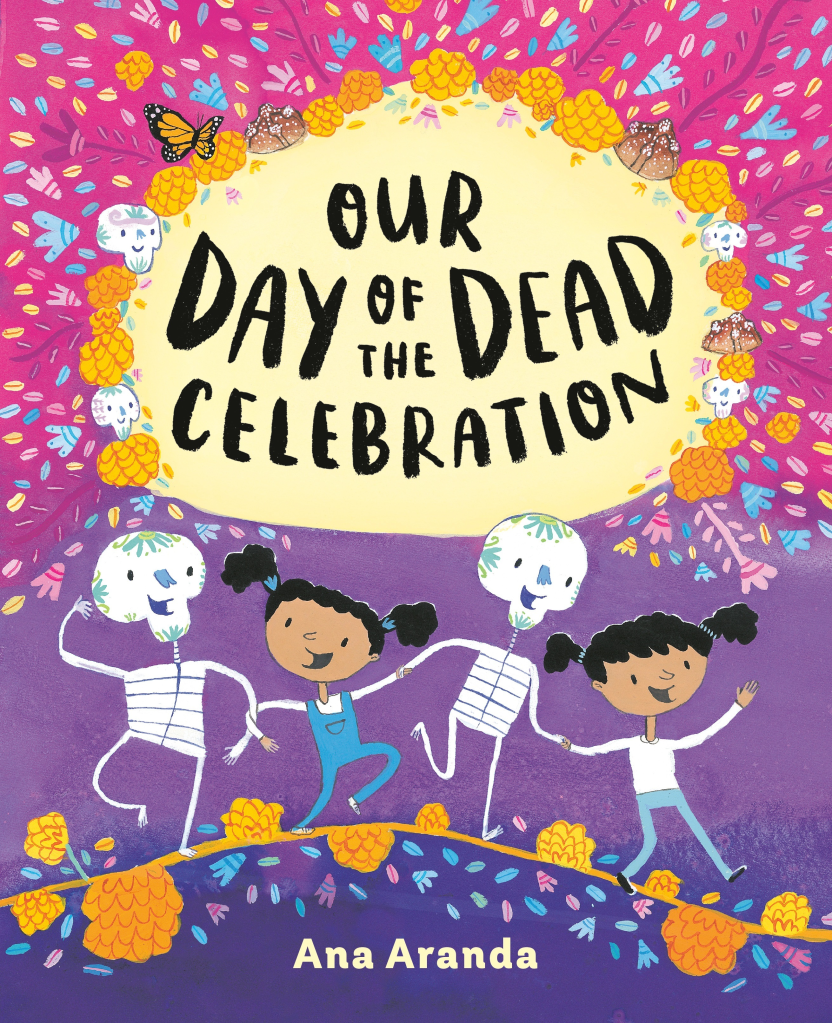

DESCRIPTION OF THE BOOK: When three very different girls find a mysterious invitation to a lavish mansion, the promise of adventure and mischief is too intriguing to pass up.

DESCRIPTION OF THE BOOK: When three very different girls find a mysterious invitation to a lavish mansion, the promise of adventure and mischief is too intriguing to pass up.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:  ABOUT THE REVIEWER: Cris Rhodes is an assistant professor of English at Shippensburg University of Pennsylvania. She teaches courses of writing, culturally diverse literature, and ethnic literatures. In addition to teaching, Cris’s scholarship focuses on Latinx youth and their literature or related media. She also has a particular scholarly interest in activism and the ways that young Latinxs advocate for themselves and their communities.

ABOUT THE REVIEWER: Cris Rhodes is an assistant professor of English at Shippensburg University of Pennsylvania. She teaches courses of writing, culturally diverse literature, and ethnic literatures. In addition to teaching, Cris’s scholarship focuses on Latinx youth and their literature or related media. She also has a particular scholarly interest in activism and the ways that young Latinxs advocate for themselves and their communities. DESCRIPTION OF THE BOOK (from

DESCRIPTION OF THE BOOK (from

ABOUT THE AUTHOR (from

ABOUT THE AUTHOR (from  ABOUT THE REVIEWER: Katrina Ortega (M.L.I.S.) is the Young Adult Librarian at the Hamilton Grange Branch of the New York Public Library. Originally from El Paso, Texas, she has lived in New York City for six years. She is a strong advocate of continuing education (in all of its forms) and is very interested in learning new ways that public libraries can provide higher education to all. She is also very interested in working with non-traditional communities in the library, particularly incarcerated and homeless populations. While pursuing her own higher education, she received two Bachelors of Arts degrees (in English and in History), a Masters of Arts in English, and a Masters of Library and Information Sciences. Katrina loves reading most anything, but particularly loves literary fiction, YA novels, and any type of graphic novel or comic. She’s also an Anglophile when it comes to film and TV, and is a sucker for British period pieces. In her free time, if she’s not reading, Katrina loves to walk around New York, looking for good places to eat.

ABOUT THE REVIEWER: Katrina Ortega (M.L.I.S.) is the Young Adult Librarian at the Hamilton Grange Branch of the New York Public Library. Originally from El Paso, Texas, she has lived in New York City for six years. She is a strong advocate of continuing education (in all of its forms) and is very interested in learning new ways that public libraries can provide higher education to all. She is also very interested in working with non-traditional communities in the library, particularly incarcerated and homeless populations. While pursuing her own higher education, she received two Bachelors of Arts degrees (in English and in History), a Masters of Arts in English, and a Masters of Library and Information Sciences. Katrina loves reading most anything, but particularly loves literary fiction, YA novels, and any type of graphic novel or comic. She’s also an Anglophile when it comes to film and TV, and is a sucker for British period pieces. In her free time, if she’s not reading, Katrina loves to walk around New York, looking for good places to eat.

Aren’t children too young to think about social and political issues? Should we interfere with children’s innocence by prematurely exposing them to the darker sides of life?

Aren’t children too young to think about social and political issues? Should we interfere with children’s innocence by prematurely exposing them to the darker sides of life?  Joelito’s Big Decision/ La gran decisión de Joelito

Joelito’s Big Decision/ La gran decisión de Joelito Our book tells the tale of Joelito, who eats dinner at MacMann’s Burger Restaurant with his family every Friday. The story begins one Friday when he finds his best friend Brandon and Brandon’s parents at the restaurant entrance, holding up signs saying, “Low Pay is Not OK,” and “Fight for 15,” and urging the hungry Joelito not to eat at MacMann’s tonight.

Our book tells the tale of Joelito, who eats dinner at MacMann’s Burger Restaurant with his family every Friday. The story begins one Friday when he finds his best friend Brandon and Brandon’s parents at the restaurant entrance, holding up signs saying, “Low Pay is Not OK,” and “Fight for 15,” and urging the hungry Joelito not to eat at MacMann’s tonight. Hope

Hope Author Ann Berlak has been a teacher and teacher educator for over fifty years. She envisions schools as places where children learn to become active, caring participants in the creation of a world that works for everyone. Joelito’s Big Decision/La gran decisión de Joelito was selected for the 2016-2017

Author Ann Berlak has been a teacher and teacher educator for over fifty years. She envisions schools as places where children learn to become active, caring participants in the creation of a world that works for everyone. Joelito’s Big Decision/La gran decisión de Joelito was selected for the 2016-2017  As important as it is to contest happy endings, it is also important to protect Latino children’s right to happiness. I became more aware of this significance upon giving a presentation on Juan Felipe Herrera’s Super Cilantro Girl where I was asked if the story’s ending undermined Esmeralda’s agency. Super Cilantro Girl tells the story of Esmeralda Sinfronteras and her transformation into a giant green superhero set to rescue her mother from an ICE detention center. Upon learning that her mother has been detained at the border, Esmeralda taps into the power of cilantro and gradually changes into Super Cilantro Girl. Bigger than a bus, taller than a house, and with the power of cilantro and flight, Esmeralda breaks her mother out of the detention center and brings her home. Super Cilantro Girl disrupts the anti-immigration policies that seek to separate her family by becoming bigger, stronger, and more heroic than the system. At the end of the story, however, it turns out that Esmeralda was dreaming and did not change into Super Cilantro Girl nor did she rescue her mother. Despite that, though, Esmeralda’s mother returns. In my presentation, I claimed that Esmeralda’s transformation exemplified how the body can be a site of healing. What does the ending then suggest about Esmeralda’s healing process and agency if her transformation into a superhero was just a dream? It was then suggested that I’d have a more productive reading of Super Cilantro Girl if I talked about it as magical realism and/or science fiction.

As important as it is to contest happy endings, it is also important to protect Latino children’s right to happiness. I became more aware of this significance upon giving a presentation on Juan Felipe Herrera’s Super Cilantro Girl where I was asked if the story’s ending undermined Esmeralda’s agency. Super Cilantro Girl tells the story of Esmeralda Sinfronteras and her transformation into a giant green superhero set to rescue her mother from an ICE detention center. Upon learning that her mother has been detained at the border, Esmeralda taps into the power of cilantro and gradually changes into Super Cilantro Girl. Bigger than a bus, taller than a house, and with the power of cilantro and flight, Esmeralda breaks her mother out of the detention center and brings her home. Super Cilantro Girl disrupts the anti-immigration policies that seek to separate her family by becoming bigger, stronger, and more heroic than the system. At the end of the story, however, it turns out that Esmeralda was dreaming and did not change into Super Cilantro Girl nor did she rescue her mother. Despite that, though, Esmeralda’s mother returns. In my presentation, I claimed that Esmeralda’s transformation exemplified how the body can be a site of healing. What does the ending then suggest about Esmeralda’s healing process and agency if her transformation into a superhero was just a dream? It was then suggested that I’d have a more productive reading of Super Cilantro Girl if I talked about it as magical realism and/or science fiction.